Dear Detroit students, parents, educators and community members,

My name is Nate Mullen and I am a special advisor at People In Education, a project that works to humanize schooling through facilitating spaces for reflection, curiosity and connection.

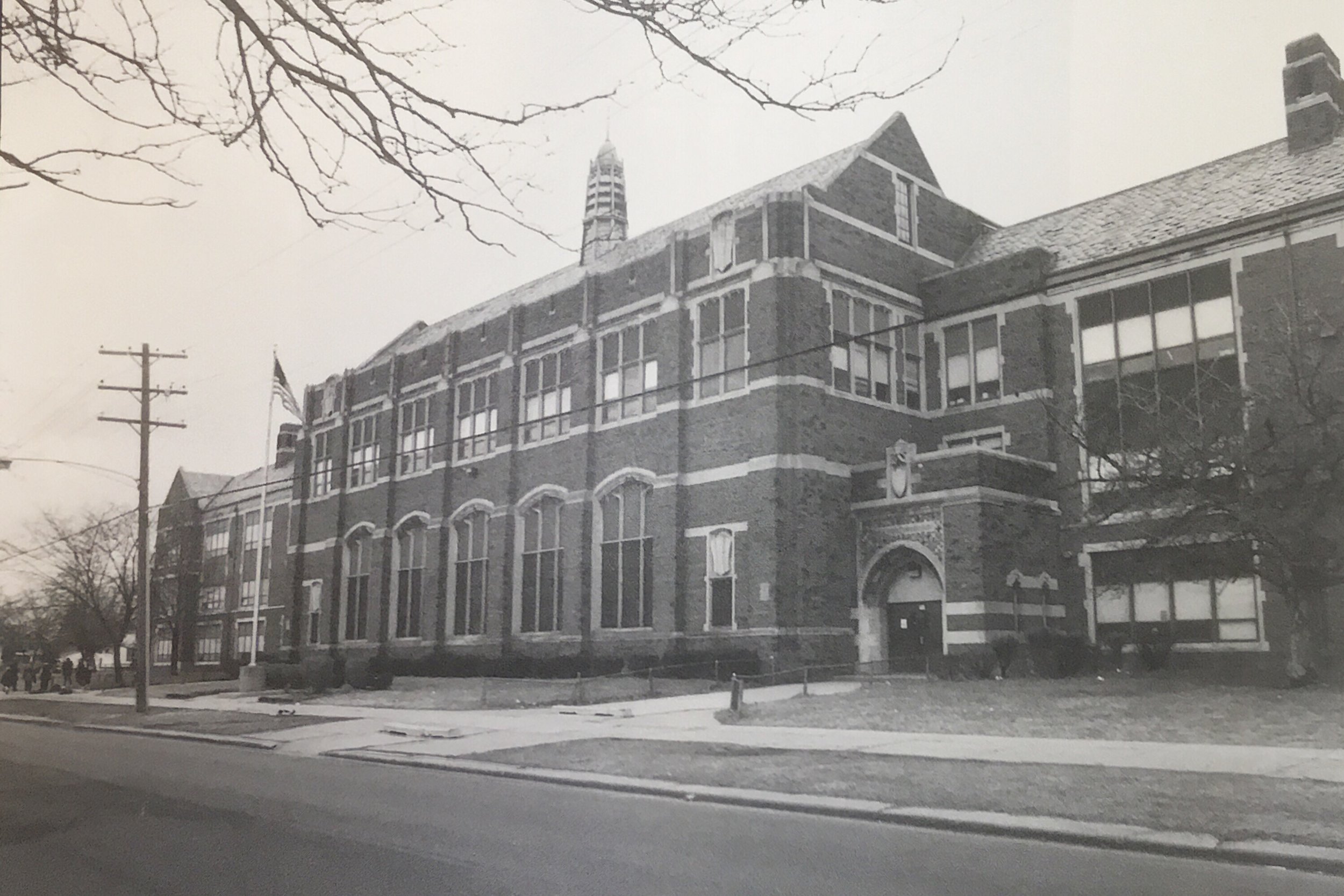

Nate Mullen, People in Education Special Advisor, in 6th grade at Hutchins Middle School

Nineteen years ago, you would have found me just off Clairmount and Woodrow Wilson in the North End, a sixth grader at Hutchins Middle School. I had the crisscross haircut, I was really into my grades and I was not cool. I’ll never forget the day I got my first 4.0 report card-- when school let out, I took off running as students spilled out into the neighborhood. Hutchins was a block away from Sanders Elementary, so the streets were choked with students, parents, aunties and siblings. That day I ran, in my uniform white shirt, dockers and rockports, past the crowds and down Clairmount. It was the 'hood, without a doubt, but it was beautiful; it was just turning spring, there weren’t any stray dogs and I had my first report card with all As.

If you make your way down to Woodrow Wilson today, you won’t see crowded streets - you’ll see Hutchins standing big, beautiful and empty. The school sits vacant, like an ancient ruin. And you won’t find Sanders Elementary anywhere. The school that sat behind Hutchins is gone, as if it never was there.

“ We must change our idea and practices of education - by asking new questions, by centering the lives of our young people and by putting relationships at the heart of our schools.”

This emptiness, for me, is actually painful. It's not only the personal pain of wishing I could show my daughter the places of my childhood. It’s a collective pain, because this story has played out in nearly every neighborhood of Detroit. Over the last 17 years, more than 230 schools have closed or been reconfigured. The decaying buildings and empty fields that remain offer painful, but important lessons. They tell stories, not only of population loss and economic upheaval, but of a dying model of education. I was educated inside of an education model that told me and my peers that if we went to school and worked hard we would graduate, go to college and find a job. This education model worked for a small percentage of students like me and it failed many, many more. It has never been clearer to me that whether we “succeed” in this model of education or not, it is failing all of us.

When I look at my experiences in school, too often the skills that were honed were about a submission to the status quo. I learned to be quiet and allow the adults do the talking. I learned that my grade, which is assigned by my teacher, was my value. I learned that it was often better to compete rather than collaborate, because collaboration was either a detriment to my grade, or worse-- punishable as cheating. I was able excel at these skills, and because of that, I was offered opportunities. But these are not the skills we want to impart to our young people. Our practice of school rewards those who submit to power, and punishes bold individuals. We need to reexamine this idea, which is at the heart of our current education model.

Everyday that we continue this model of education, we harm our community, our city and our children. We must change our idea and practices of education - by asking new questions, by centering the lives of our young people and by putting relationships at the heart of our schools.

Asking new questions

Our current debates about education center around academics, test scores, school choice, etc. These conversations are without a doubt important, but they often obscure the fact that education is an endeavor of humanity, not of our economy. Test scores and academics are important, but ultimately they work as a metric to guarantee that our schools will produce a capable workforce. However, school isn’t just a place where we train workers; it is a place where we nurture our children and where they learn to navigate and shape the world they live in.

Whenever I give a talk about our work, I ask the audience to participate in a practice we use in the classroom. I ask them to hold a debate. Debates are a practice wherein the students get to hold the floor and the teacher steps back, shifting the way power usually works in a classroom. Two signs are posted in the room, on opposite walls, one reads “Agree” the other “Disagree”. I give the group a statement and ask them to choose a side that most closely aligns with how they feel about the statement. The statement we use in workshops is “a quality education is within reach for everyone.”

A debate at the 2016 Rida Institute Summer Retreat

In the process of debating this statement, three things usually emerge. First, the group realizes that not everyone has the same idea of what a “quality education” is. This realization leads the group to ask, how can our schools offer a “quality education” if we don’t even agree on what that is? Shorty after, the second point emerges; folks start to say “Well, education isn’t really limited to our schools...? It lives in our communities or in conversations with our elders.” This, like the first moment, forces us to reckon with assumptions that education only lives in our schools. This leads us to the final point, when the group starts to ask "If education isn’t limited to schools, then what is the purpose of school?"

This is why we use this statement - because it moves the conversation past the immediate issues and to the core questions:

“How do we as a society understand what makes for a quality education?”

“If education can happen anywhere, what’s the purpose of school?”

These questions are a better place to start a conversation about education.

Centering the lives of our young people

To answer these questions, we start with the experts, our students. Every year, as part of our evaluations, we interview students from the classrooms in which we work. One of our recurring questions is: “What is the purpose of education?” In a 4th/5th split classroom, one student said, "The purpose of education is for you to learn or know things, so you can have these preparations, or whatever the teacher is teaching.” A second student sums up the point “so basically she’s saying that you'll know what you're doing when you get older.” In a high school classroom, a graduating senior said, “I think it’s to teach you stuff that you need to know in your career, that you’re going into after you finish school. Like say, you want to be a scientist, so you learn science stuff in school. ”

Do you notice that all of these answers are about the future? They are about "when you grow up," meaning that what is happening in the classroom might matter in the future, but not now. Grace Lee Boggs, one of the inspirations behind our work, wrote about this in her book The Next American Revolution. She quotes John Dewey, one of the great thinkers on American schooling: “Dewey insisted that education is ‘a process of living and not preparation for future living.’ He called for the school to ‘represent present life — life as real and vital to the child.’” She goes on: “From the standpoint of the child, Dewey concluded ‘the great waste in school comes from his inability to utilize the experience he gets outside the school in any complete and free way within the school itself; while on the other hand he is unable to apply in daily life what he is learning in school. That is the isolation of the school — its isolation from life.’”

It's clear from the student interviews that this isn’t news to students. They know that school isn’t about them, it's about some future version of them.

For me, I really struggle with this when I think about the fact that by the age of 30 I have gone to three memorials for my classmates from high school, when I think about the rash of youth violence in this city, and when I consider that more than 50% of the young people in this city are growing up in poverty. I have to ask: do our students have the luxury to wait until they “grow up” for school to matter?

How can we transform schools to be spaces that reflect life? How can we make them spaces that are “real and vital” as Dewey says?

Putting relationships at the heart of our schools

PIE student reserachers presenting their research at Free Minds Free People in 2015

For us at People In Education, the answer lies in humanizing our schools. As part of the research carried out by our youth researchers, they asked young people from around the city the following question: “what are the most humanizing aspects of school?” The answer, over and over again was, deep and caring relationships: "my relationships with my friends," "my relationship with my teacher, who I know really gets me," "my relationship with the administrator that says hello to me everyday.” Rather than thinking that the answer to our education crisis lies solely in academic practices or more funding, People in Education wants to shift the focus to looking at the relationships between the people in and around schools.

These findings are affirmed by what scientists are learning about our brains, by what education researchers are learning about effective teachers, and by what we’ve always known-- that caring relationships make all the difference.

If we look at how the brain works, we see that relationships are essential to healthy development. In the book the Developing Mind, psychiatrist Daniel Siegel writes, “Interpersonal experiences directly influence how we mentally construct reality. This shaping occurs throughout life, but is most crucial during the early years of childhood.” Second to the home, school is where our children are creating many of these interpersonal experiences that directly shape how their brains develop physiologically.

We also know that health outcomes can be correlated to caring relationships. The more caring relationships people have, the better the health outcomes, meaning they live better, longer lives when they have these relationships. All of this is made more urgent in the context of our city, where many of our youth grow up in poverty and experience high levels of toxic stress. If schools are places where young people refine skills to build caring relationships, these skills can actually lead to our young people living happier, healthier lives.

“when we limit the role of schools to primarily teaching subjects such as reading, writing and arithmetic, we’re missing the point. Students need to learn much more than academic content— they need to learn how to be in the world.”

This means that when we limit the role of schools to primarily teaching subjects such as reading, writing and arithmetic, we’re missing the point. Students need to learn much more than academic content-- they need to learn how to be in the world. This idea of school urges isolation over connection.

This is why we work to create spaces that foster connection, curiosity and reflection. Whether it is through our in-school project where we facilitate student-led community investigations using media, or the Rida Institute, our yearlong training to help build a supportive community among teachers who want to rewire power dynamics in their classrooms, PIE understands that connection is essential to our humanity.

In an interview, one of my inspirations Carla Shalaby calls for us to “use classrooms as an opportunity for young children to imagine and to practice a better way.” Through People in Education, we hope to do this by creating spaces to ask new questions about the purpose of school, centering the lives of our young people and placing relationships at the heart of our work.

Love,

n8

Nathaniel Mullen is the former director and current special advisor to People In Education. Nate’s work thrives at the intersection of art, education and people. For more than a decasde, Nate has worked in classrooms, leading student media investigations which have included everything from stop motion videos about Newton's Laws to infographics on the complexities of global economics. He has a B.F.A. from the University of Michigan and is a graduate of Detroit Public Schools.